Bridging the Divide

What is driving the realignment in UK politics?

The country is more progressive. So why is the left losing?

According to most measures, the UK population is further to the liberal left than a generation ago. Social attitude polling would attest to this — on questions such as gender, race, sexuality and the environment. And research by Paula Surridge finds that both main parties’ voter bases moved gradually to the left on economic issues too, between 1992 and 2019. People are, on balance, more committed to equality, sustainability and fairness.

Yet a curious cocktail of factors means that, in spite of our more liberal electorate, social conservatives appear to be winning. This was demonstrated by the decision to leave the EU in 2016. But it has also led to the near-hegemonic position which Boris Johnson’s Conservatives now hold at Westminster. The increasingly progressive attitudes of the UK population are not being reflected by our politics.

The same is true of a number of other Western democracies, with many social democratic parties out of power. But a combination of Brexit, the UK’s greater regional inequalities, and the arithmetic of First Past The Post (FPTP) means it has hit British progressive parties especially hard. Our politics has shifted to the right, culturally — just as the populace has shifted to the left.

Two intertwined elements help to explain the apparent contradiction at play: an electoral realignment within the country, accelerated by Brexit; and a ‘culture war’ debate, played out online and in the media. Both of these phenomena undermine progressive shifts in public opinion.

The first element describes the fact that, while almost every part of the UK has moved in a progressive direction, many areas are only a bit more progressive than they were a couple of decades back, whereas a few are significantly more so. The ‘mean average’ Westminster seat is, I think, decidedly more socially liberal. But the ‘range’ between the most and least liberal has expanded (although even the least liberal is, I suspect, more liberal than a generation ago).

Places which have become a bit more liberal electorally outnumber those that have become a lot more so, thanks in part to demographic shifts. The most pronounced types of left liberalism increasingly coalesce in a comparatively small number of urban centres. In particular, younger people have migrated towards cities.

Bohemian enclaves and networked hubs of this kind now seem to talk a different language to other areas — even when they mean the same thing. Labour speaks this dialect fluently, but the Tories are better at communicating with everywhere else.

The second element — the culture war — creates perpetual debates around talk radio style ‘issues of the day’. Many of these are so minor as to barely matter, or else highlight differences so marginal, in the grand scheme of things, as to be academic. The discussion a few years ago about whether Jamie Oliver was guilty of ‘cultural appropriation’ for selling ‘jerk rice’ is a good example.

Yet these debates create a ‘narcissism of small differences’, percolating into national newspapers and day-to-day conversations and magnifying divides. And the left is again at a disadvantage here. Unlike the Tories, Starmer’s party has been unable to find a place for itself in the aggressive social media debates which the culture war often entails, without cutting itself further adrift from the seats it needs to win back.

The second factor effectively works to amplify and inflame the first. Each cultural wedge issue reinforces the wider realignment, inviting people to take either-or positions and dividing the quite liberal from the very liberal. This means that ultra-progressive parts of the population have become estranged from everyone else, geographically and digitally, at precisely the point where they need to bring others with them.

The challenge for Labour, therefore, is both to reverse an electoral readjustment which many now regard as inevitable, and to ‘bridge’ an increasingly binary set of culture war debates.

The analysis below is an effort to map out Labour’s current predicament— as the party gathers for its first in-person conference since the 2019 General Election. It looks, first and foremost, at the electoral realignment, but has clear implications, I think, for the question of how Keir Starmer approaches the culture war.

Mansfield to Lewisham

UK politics is undergoing a dramatic change. Labour lost its ‘Red Wall’ in 2019. And the 2021 local election results saw the party cede further ground in its heartlands — while making some surprising gains in liberal middle-class areas.

The shifts at play generally harm the left. It is true that there are a number of Tory held seats which might be attainable for Labour or the Lib Dems in the not-too-distant future — the ‘Blue Wall’, as analyst Steve Akehurst has dubbed it. But the socially conservative right have, overwhelmingly, been the beneficiaries of the realignment.

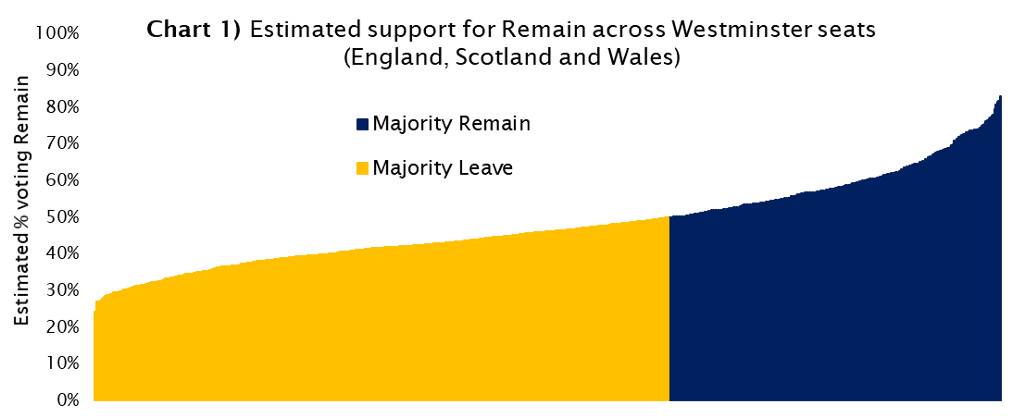

Chart 1 shows part of the reason why. It visualises the structure of the 2016 Remain vote across all UK constituencies, as estimated by Chris Hanretty (figures here). Whilst I think Brexit is overstated as a primary cause for the realignment, looking at the makeup of the referendum vote is helpful, as a proxy for the distribution of liberal attitudes.

As we can see, there are many more majority-Leave seats than majority-Remain. Whereas the Leave-Remain ratio in 2016 was 52%-48% in terms of votes, it was 64%-36% in terms of Westminster constituencies (according to Hanretty’s deductions). The Remain campaign triumphed in fewer seats, but won by more handsome margins in those which it did win — hence why the final result was so close. If you take Scotland out of the equation, this pattern becomes even more pronounced.

Chart 1 is an indictment of FPTP. But it speaks to more than just a critique of our voting system. It illustrates, at a deeper level, that the strongest liberal attitudes are not spread evenly across the country.

Chart 2, below, depicts the seat-by-seat cumulative swing from Labour to Tory and vice versa, during the 2010s. It essentially treats the period between 2010 and 2019 as if this were a single electoral term, rather than three. (This is based on the data behind my ‘Against their interests’ article earlier this year. It looks, for reasons of consistency, at English seats only — as some data, such as that for deprivation, is not directly comparable with the other UK nations).

There are 533 constituencies covered, the swing for each of which is shown in the chart. The seat with the biggest cumulative swing from Labour to the Conservatives is Mansfield (23% points). The seat with the biggest cumulative swing the other way — once you set aside the slightly unusual case of Bradford West, George Galloway’s old stamping ground — is Lewisham West and Penge (22% points).

The 2010 and 2019 elections were both, we should remind ourselves, bad nights for Labour — although 2019 was obviously worse. But what we have seen, during the intervening nine years, is a dramatic re-ordering, beneath the surface, in terms of which parts of the country Labour can rely on and where its appeal lies. This extends far beyond the 43 additional English seats which had been lost by 2019.

The differences in trajectory are immense, in many cases. Mansfield saw a 6,012 Labour lead over the Conservatives in 2010 become a 16,306 Tory majority in 2019. In Lewisham West and Penge, by contrast, Labour’s 7,012 advantage over the Tories at the start of the decade had trebled by the time of the last General Election, to become a thumping 21,543 majority.

In total, 304 English seats swung to the Tories between 2010 and 2019, whereas only 227 swung towards Labour — the Conservatives having started the 2010–19 period in government, let’s not forget. And 75 seats swung Tory by 10% points or more, whereas just 49 swung to Labour by the same margin. Both of these lists of places are shown below.

The fact that Labour increased its majorities in a large number of areas during the 2010s is overlooked, during a decade that is seen as one of all-out decline for the party. These advances should not be underplayed or taken for granted, but they also provide scant comfort.

The simple fact is that, unless a significant number of the seats that have been shifting Tory for the past few years begin to swing back towards Labour, then there is no route to power for the party in the foreseeable future.

It was hoped that by choosing Keir Starmer — a less contentious leader than Jeremy Corbyn — the divergence at play could be averted and the Red Wall won back. While things have improved, this has not happened so far. The risk, if the present realignment continues, is that Labour racks up ever more votes in an ever smaller number of cosmopolitan centres, and is consigned to eternal defeat elsewhere.

The idea of a ‘progressive alliance’ often acts as a balm here. It implies that liberal progressives of all kinds can club together and win. Assuming that this idea goes beyond case-by-case cooperation, then there are many practical questions to be asked of it. These have been made by others and I will not go into them here. But the chief objection I can see — even if the arithmetic panned out perfectly and the policy differences between left parties were overcome — is that the ‘progressive coalition’ proposal does not seek to reverse the realignment above, or even to properly acknowledge it.

Former Labour heartlands have not been lost to the Greens and the Lib Dems — or even, in the main, thanks to Green and Lib Dem parties splitting the progressive platform. The Greens did not stand in Mansfield in 2019, and the Lib Dems won just 1,626 votes. There are some seats, with very small swings to the Tories, where the amalgamated votes of progressive parties outnumber those of the Conservatives. But, generally speaking, the progressive coalition idea accepts by implication that many of the country’s poorest communities — those who are supposed to benefit from progressive politics, and where Labour used to be strongest — are now lost to the Conservatives forever. According to this plan, the left acts in the interests of those who will never vote for us.

The role of education

You can immediately see, from the above lists of constituencies, that those swinging to the Tories are distinct sorts of place from those going to Labour. But what makes them different? Why are certain sorts of place likely to be pushed in one electoral direction by the so-called culture war, while others go the opposite way? What is it, exactly, which means that Mansfield has become an impregnable Tory fortress whilst, over the same time span, Lewisham West and Penge has become a place which weighs the Labour vote?

Does the difference come down to deprivation? Not really. Mansfield is the 117th most deprived English seat, of 533, and Lewisham West and Penge is the 192nd. Seats swinging to the Tories are, it is true, more deprived. But there are countless outliers. Manchester Central is the 17th most deprived constituency in England, but has seen a 7% point cumulative swing to Labour. So, the explanation for the realignment is not purely about poverty and wealth.

Chart 3 looks at the proportion with no qualifications and with no degree in all English seats. It then breaks this into quintiles, and shows the average 2010–19 cumulative swing in each of the quintiles. As we can see, the highest quintiles for no qualifications and no degree — i.e. the 20% of English seats that score highest for each — have cumulative shifts towards the Tories of 6.46% points and 7.08% points, respectively. Whichever of the two definitions we are using, the least educated areas have swung Conservative in the most extreme way.

This pattern plays out neatly as you go down the quintiles. The lowest 20% of seats for no qualifications and no degree — i.e. the most educated fifth of constituencies, according to these two definitions — have swung towards Labour in a similarly dramatic fashion (by 5.24% points and 5.68% points, respectively).

Polling elsewhere has found this, with Boris Johnson’s appeal, in particular, being heavily swayed by education level. His approval rating, at the end of the pandemic, was +17 among those with no qualifications, and -26 among those educated to degree level.

This certainly helps to shed some light on the ‘Mansfield versus Lewisham’ conundrum: 16% have a degree in the former, compared to 37% in the latter.

When we compare education with other factors we find, at a constituency level, that low education correlates with Tory swing more exactly than other potential metrics. Chart 4 shows the ‘no degree’ quintile figures from Chart 3, next to datasets which provide four other potential explanations for the factors which might be driving the realignment: social class (blue bars), ethnicity (orange), age (brown) and deprivation (pink).

Deprivation correlates only slightly with Tory swing. But in the case of class, ethnicity and age, there are also strong parallels. If a seat has:

a) a below average number of graduates

as well as

b) an above average proportion in social grades C2DE

c) an above average proportion of white British heritage and

d) a higher than usual average age

then odds on it will be Tory held or moving in that direction.

Of 123 English seats which fit this description, 99 are now Tory held (as of the Hartlepool by-election in April), compared to 67 in 2010. And, in total, 107 of these 123 places have swung towards the Conservatives since 2010. The 16 places that are bucking the trend and swinging to Labour are mostly in the South West — where the collapse of the Lib Dems has created an unusual dynamic. And a few are in Merseyside — perhaps now the only part of England where the working-class aversion to voting Tory remains strong.

It is important to stress, however, that degree education correlates more strongly than class, ethnic makeup or even age. If we were to draw trend lines onto Chart 4 for these metrics, they would all be a little flatter than the green trend line I have mapped on for ‘no degree’.

Indeed, I wonder if education acts as a sort of a priori to some of the other factors. C2DE voters swinging Tory are less likely to have high academic qualifications, for example. Older voters are more likely to have left school at 16 or earlier, having grown up in an era when very few went to university. And the same dynamic may even be at play with the ‘white British heritage’ metric (at the last census foreign-born residents were found to be better qualified, on average, than those from the UK).

Chart 5 corroborates the central role which education plays, using a different dataset. It looks at the seven ‘domains’ used by the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD). These are the specific types of deprivation which feed into the IMD score for each area.

One of these domains is ‘educational deprivation’. Again marked in green on the chart, this definition of deprivation is based on attainment across different school key stages, as well as on school standards, absence rates, adult skills, literacy, access to training, routes into further education, etc. (Detailed explanations of the 2019 IMD domains are here).

We can see, once again, the same pronounced correlation. Constituencies in the top quintile for educational deprivation have seen a cumulative swing of 5.19% points to the Tories. Seats in the least deprived quintile for this metric have seen a 3.70% point swing to Labour.

There are correlations, too, with a swing to the Conservatives when it comes to employment deprivation (in yellow), and to income deprivation and health deprivation (in blue and grey respectively). But none of these are as strong as that for educational deprivation.

It is also worth noting, by way of a contrast, that with two of the IMD domains — living environment (red) and housing/service access (purple) — there is the precise opposite dynamic. Places which are deprived according to these definitions have been swinging to Labour in significant numbers since 2010. Areas with more crime deprivation are also a little more likely to be swinging to Labour.

Within this, we can see a national dynamic at play which is heavily informed by regional inequality and by the dominance of city hubs. In essence, deprived communities who live away from these hubs have worse employment prospects and life chances, with a lack of skilled jobs and few opportunities for training or other types of progression. Your likelihood of being on benefits or income support will probably be higher, and your life expectancy may be lower.

But deprived groups who live within city hubs do not necessarily enjoy a gilded life either: they inhabit crowded, built-up areas, with an impossibly competitive housing market, high homelessness, pollution and a lengthy queue for the library or the doctor’s waiting room. They are slightly more likely to be the victim of a crime and much more likely to be hit by a car or experience pollution.

Put crudely, poorer communities in about two thirds of the country cannot get a decent job and those in the other third cannot get a decent house. The former are swinging Tory and the latter Labour.

Ashfield, Redcar and Barnsley East, for example, are all in the top quintile for educational deprivation and for employment deprivation, but in the bottom quintile for housing/ service deprivation and living environment deprivation. These places have seen cumulative swings to the Tories of 13% points, 14% points and 10% points respectively. In Streatham, Chelsea and Fulham and Bristol West, by contrast, roughly the reverse is true — acute housing deprivation, but a wealth of opportunities. These constituencies have seen swings to Labour of 7% points, 9% points and, in the case of the latter, a whopping 21% points.

This points to quite big questions in terms of who Labour is really ‘for’ — given that the nature of deprivation is so different in different parts of the country. As Glen O’Hara wrote in a blog back in 2017, “Whose thinking is really, really ‘Labour’? The seventy-year-old ex-factory worker in Lincolnshire who owns his own house outright, or the thirty-year-old graduate mortgage broker renting out a tiny room in South-East London?”

However, the aspect which I think is most interesting here remains education. This seems to consistently overlay almost perfectly with cumulative swing. Chart 6, which visualises the above data in a slightly different way, reiterates the point. It shows, for all English seats, the proportion with no qualifications on the vertical axis. And it shows the cumulative 2010-19 swing to or from the Conservatives on the horizontal axis. The colour of the respective dots indicates the party which currently holds each constituency.

As the trend lines show, for Tory and Labour held seats alike, fewer qualifications means a greater swing to the Tories. At present, 63 of the 75 seats swinging to the Tories by 10% points or more have at least 25% with no qualifications. This is true of just 5 of the 49 seats swinging to Labour by the same margin.

Just in case it needs to be said, none of these findings vindicate or ‘prove right’ those who support liberal and left-wing causes. Education and intelligence are quite different from each other, and the electoral instincts of degree-holders are no more important to the makeup of our democracy those of voters with no qualifications.

Conclusions

The level of educational opportunity in an area appears to be a primary driver — if not the primary driver — of our electoral realignment. And it seems likely that it impacts on the sides which people take in the resulting culture war, too. Those who are not degree-educated are less likely to have heard of the term ‘woke’ or to identify with it, for example. And they are much more likely to feel that the pace of cultural change is too fast.

A huge question for progressives is precisely why this disconnect has opened up — and why now? Wider analysis reveals a similar pattern in a number of Western democracies. So the phenomenon is not unique to Britain or the British left — although it is arguably more electorally challenging. But it is as acute here as anywhere, and the shifts in the past decade are particularly striking.

Policy priorities have perhaps played a part — see, for example, the preoccupation under Corbyn with free higher education, rather than with adult skills or early years. Likewise, the academic and public sector leaning in the party’s membership may have contributed.

But to my mind basic communication is the biggest issue. Labour’s pitch to non-graduates has been uniquely tin-eared and high-handed, during the past decade. There has been little effort to persuade or bring others along, with progressive ideas regarded as self-evidently superior.

The grating activist demand that people “go away and educate themselves” epitomises the worst of this tendency. This phrase has echoes, to my ear, of Norman Tebbit’s call for the unemployed to ‘get on their bikes’ and go off to find work — placing responsibility squarely on the shoulders of the individual. If you are of the view, as I am, that a central responsibility of the state is to educate people to the best of their capacity, then this phrase should not sit comfortably with you.

The image at the top of this article shows the thrown finger of Alan Sugar, in the board room of The Apprentice. Research by Labour strategist Deborah Mattinson, for her book Beyond the Red Wall, identifies Sugar as one of several public figures favoured by working-class ex-Labour voters as an ideal national leader — were they to pick someone from outside politics. As a wealthy Remainer, a member of the House of Lords and a man who appears to spend his time circling The Shard in a helicopter, Sugar should not, on paper, be appealing to Brexit voters, communities in former industrial heartlands, or those suspicious of the ‘Westminster bubble’. But his straightforward way of explaining himself is a world away from the jargon which some progressive have been drawn to, and the fact that Red Wallers are so much more positive about him than about anyone related to the Labour Party should give us pause for thought.

It is a terrible indictment of Labour that it has alienated parts of the country where the absence of life chances, educational opportunities and job prospects is most acute. I am sure that many would have other explanations besides mine for why it has happened. But the question, as delegate descend on Brighton this week, is what Labour can now do, to re-connect with the groups lost and to escape from the electoral corner which the party is currently painted into.