Understanding Micawber’s Law

This piece is a deep dive into the psychology of debt, the metaphor of the household budget, and how this has come to affect social democratic politics in 2026. It is based on my observations from focus groups over several years.

—

“Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen and six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pound and six, result misery.”

So speaks Wilkins Micawber, one of Charles Dickens’ great comic creations, in an elegant explanation of how household finances work. A relatively small amount makes the difference between a life lived in the black and one lived in the red, Micawber explains. Success depends on staying the right side of the line.

A perennial spendthrift, Micawber fails to live up to his own maxim. His problem is not that he can’t earn but that he can’t budget. For much of David Copperfield he’s in and out of debtors’ prisons as a result.

Micawber is kind, with liabilities the result of benevolent impulses. And he’s an irrepressible optimist, famously sure “something will turn up” to bail him out. (Indeed, this characteristic has seen ‘Micawber-ism’ become a shorthand, among political commentators, for the groundless economic optimism and short-termism of our leaders).

You might like to go for a drink with Wilkins Micawber, in other words – especially as he’d likely offer to pay. You might admire his generosity of spirit. But you wouldn’t trust him to guard your savings.

Micawber’s motto helps us to navigate one of the abiding metaphors of modern British politics: the household budget analogy for the national finances. This has been the subtext to almost all Conservative economic messaging in the modern era.

Margaret Thatcher repeatedly used the trope to describe her preferred political economy. “It’s taken a government headed by a housewife with experience of running a family to balance the books…with a little left over for a rainy day,” she said in 1988.

And David Cameron and George Osborne deployed it to great effect two decades later, via the ‘maxed-out credit card’ attack (see below). The national deficit – which in reality was due to a global banking bailout – was blamed on an over-lavish state. Austerity followed.

During the Corbyn years, meanwhile, Labour was relentlessly mocked for its supposed belief in a “magic money tree” to pay for ideas like free broadband. This was a charge which stuck.

Labour, the Conservatives thus say, are the political equivalent of Wilkins Micawber: generous to a fault and, therefore, unable to balance the books. Labour politicians know, like Dickens’ character, that you must budget in theory. But their big, foolish hearts lack the discipline to carry it through in practice.

This, in a nutshell, is Micawber’s Law. And it’s a perception which Labour often reinforces by mistake. The best example here is Liam Byrne’s infamous note upon leaving the Treasury in 2010: ‘I’m afraid there is no money!’ Written in jest, as part of a tradition amongst outgoing ministers, it was cruelly leaked in the early days of the Coalition government. The episode, which is brought up in focus groups to this day, spoke to voters of the Micawber mentality writ large. Unforgivably profligate, and cheerfully so.

Labour’s failure to deal with Micawber’s Law is a big part of the reason why UK political history has been dominated by Tory governments. Indeed, social democrats’ struggle to rebut the accusation shapes the entire policy architecture of the country.

Labour politicians who are serious about power invariably feel that they must match Tory spending pledges, just to be given a hearing. They must rule out borrowing of all kinds and put a notional price-tag on every item.

If they fail to do these things – if they permit themselves even a little leeway – then they fear, with good reason, that they will end up back where Labour always seems to find itself: as Micawber, the benevolent spendthrift.

Hence Rachel Reeves’ focus before the last election, quite sensibly, was on the ‘iron clad’ rules that would govern her tenure as Chancellor. “Every penny mattered,” according to Reeves, thanks to lessons learned from her mother at the kitchen table.

The fact that the household budget metaphor chimes with a conservative economic prospectus is a stroke of good luck on their part – not the product of clever messaging or ideological brainwashing. This is important to understand, and is rarely explored by the left, even amongst those who argue thoughtfully and correctly against the analogy.

The household budget metaphor is, for better or for worse, deeply intuitive. It is how most voters who do not have direct dealings with the government finances conceive of the economy. Money is almost always experienced in our own lives, after all, as something zero-sum, and this is applied automatically to the Treasury. Hence, we talk about the ‘public purse’ without thinking; we refer to leaders ‘balancing the books’, to the government ‘coffers’, and to money found ‘down the back of the sofa’ by the Chancellor.

To demonstrate the potency of the household budget analogy, it’s worth considering the alternative metaphors on offer, amongst those who back a Keynesian economic model. The most famous motif here is the idea of ‘digging a hole to fill it back in again’ – which was used by Keynes to explain how governments could stimulate a recovery during an economic slow-down.

Keynes deliberately non-intuitive allegory may be astute. Building, making and doing things can help the cogs of growth to turn again when times are tough, and it’s in the government’s interest to make this happen. But the metaphor, with its celebration of pointless and unnecessary work, does not cohere with any of the common-sense lessons which voters take from real life. It is the antithesis of the household analogy, in fact, and even on a good day it would struggle to compete with the simple idea that governments, like the rest of us, must live within their means.

Crucially, according to the household analogy, the sizes of the figures at stake are largely irrelevant. Any amount bigger than that which voters are used to dealing with in their daily or professional lives is seen in roughly the same way – be it an online public health campaign costing a few hundred thousand, a government commission coming in at a couple of million, or a multi-billion-pound hospital-building programme.

A good illustration of this is the public’s attitude to council ‘waste’. Voters despise waste and see it everywhere. Hence, the Reform right have made a populist ‘war on waste’ into their lodestar in local government.

Yet voters’ dislike of waste does not, for the most part, come from a detailed analysis of local authority accounts. They’re not calling for an overhaul of procurement policy or proposing smarter ways that a council’s social care budget could be spent.

Instead, it derives from people’s day-to-day observation of low-level misspending and folly. A small piece of public art. A set of roadworks suspected to be unnecessary. A new BoxPark that sits empty. A zebra crossing repainted with a jazzy design. An unnecessary consultation exercise. Etc etc etc. Each of these things illustrates, for many voters, a Micawber-ish lack of hard-headedness at the top of their council.

To an economist, such trifling examples may demonstrate the idiocy of the household budget analogy. Perhaps so. But they also reveal its powerful internal logic. The original Micawber quote emphasises, after all, that a small amount can make the difference. It only takes a tiny overspend to move you from black to red. Choosing to prioritise an unnecessary set of road markings or an expensive mural suggests – at a point when budgets are known to be tight – that you don’t understand this.

For many voters, Micawber’s Law is a way of reconciling their lack of fiscal knowhow. It offers a lesson from real life, to evaluate policy choices. Hence, it has thrived in an era where mainstream parties have learned to focus on bread-and-butter policy issues and to leave ideology at the door.

If Labour is promising 5,000 more teaching assistants and the Tories are promising 2,000, for instance, then the parties’ reputations for money management becomes an important rule of thumb. Often the undecided voter concludes – with regret – that the more modest offer is the more credible one.

Thus, Micawber’s Law is ultimately a question not of economics but of character. It is an error to equate voters’ faith in the household budget metaphor with a conservative ideology. Those who buy into the characterisation of Labour as Micawber are not hawks and monetarists, desperate to shrink the state.

Rather, they tend to be medium engagement, low-to-middle-income voters. Poor enough that life feels like a struggle, but ineligible for benefits and perhaps with enough savings that they have something to lose if things really go wrong.

They support the idea of a cradle-to-grave state and a safety net for those who genuinely need it. They want a fairly interventionist government and higher taxes on the very rich. And they want public services properly funded. But, for all this, they are terrified of arrears, spiralling inflation and the ball-and-chain that is debt. They worry that their taxes will be wasted, or else will be spent paying interest to creditors.

In this respect, Jon Cruddas’s 2015 characterisation of swing voters as ‘fiscally conservative but economically radical’ was a perceptive one. Those prone to Micawber’s Law believe governments should run a budget surplus at all times (as the rest of us try to do). And they expect to be told where every penny of proposed investment will come from. But they do not necessarily oppose redistribution, financial regulation, public ownership or a progressive tax system.

In 2025 we saw many of these questions come to a head. I wrote in October about the government’s reluctance to put down the ‘Ming Vase’ it had carried into the 2024 election. A large part of this early caution was rooted in a need to neutralise Labour’s historic reputation for overspending. Go into the election with an expensive promise hanging over your head and Micawber’s Law could strike once again.

The best practical example here was the decision, six months before the contest, to get rid of Labour’s £28bn borrow-to-invest plan for the rollout of clean energy. Prior to being scrapped, this was the biggest growth lever in the Starmer offer. The question of whether our economy and ability to fund public services would have fared differently had the pledge remained is an interesting counter-factual.

Alongside these sorts of policy decisions, fear of what I’m calling Micawber’s Law made the government place deep rhetorical emphasis on the Treasury’s Fiscal Rules. These rules do not, in themselves, block Keynesian efforts to stimulate the economy, via targeted spending on infrastructure. But without high profile efforts to do so – and alongside cuts to benefits like the Winter Fuel Allowance once in office – they have created a sense of deep gloom. A rhetoric which seemed, before the last election, like a necessary step to mitigate Micawber’s Law, now gives the impression of a technocratic government, straight-jacketed by its own thrift.

In the context of a majority of 174, this fuels the sense that mainstream parties either can’t or won’t act in our interests – fuelling populism.

It’s worth pausing here to remember that tax – not borrowing – was the real bone of contention within the November 2025 budget. Rachel Reeves spent the months before the budget being quizzed about whether she’d raise taxes, and the week afterwards debating whether she had technically broken Labour’s manifesto pledge not to do so.

This poses an interesting question: where does taxation fit within the household budget analogy and Micawber’s Law?

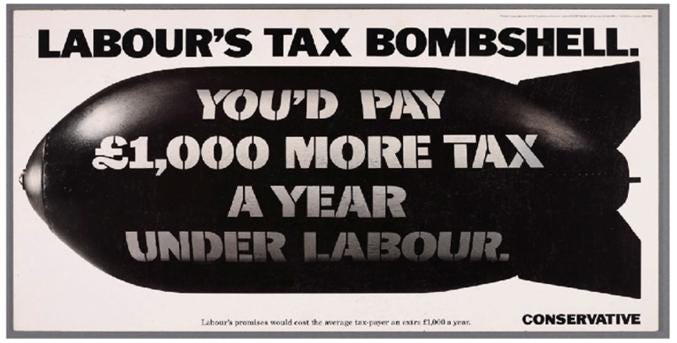

Clearly, tax is another area of historic brand weakness for Labour – and for parties of the left more generally. Any veteran of the 1992 election will likely recall the Conservatives’ notorious ‘Tax Bombshell’ poster of that year (see below), which some believe won John Major his surprise majority.

Yet the reasons for tax being a Labour brand weakness are not necessarily rooted in the household budget analogy. Rather, they stem from the separate view that progressive parties oppose aspiration. Labourites and left-wingers will instinctively punish success and stamp out entrepreneurial spirit, the charge goes.

This is an interesting voter perception, but shouldn’t automatically be conflated with Micawber’s Law. It is possible for a progressive government to be accused of overspending, for instance, without being seen as practicing the politics of envy. (See here: the public’s recollection of New Labour – which ‘got’ aspiration but is nevertheless remembered as having lived beyond its means).

But this is not to say there’s no link. The ultimate swing voter fear is that tax increases are the last resort, for an administration which has blown its budget. A Micawber-ish government eventually has to go cap-in-hand to its public and ask them to bail it out, when ‘something’ does not turn up. It’s always the voter who foots the bill in the end, our cynical electorate assumes. It’s always me and you.

Thus, two distinct things – the household budget analogy and the perception that Labour will tax you ‘till the pips squeak’ – can easily end up converging. Margaret Thatcher’s 1976 assertion that “The problem with socialism is that you eventually run out of other people’s money” is the best rhetorical example of this dovetailing.

To avoid this, progressive parties need to make it crystal clear that extra money levied from voters won’t be spent on debt, interest, or ‘robbing Peter to pay Paul’. It will go towards something worthwhile, which benefits those who are paying in.

In this light, Labour’s focus since the election on the ‘£22bn black hole’ is an error. This is especially true in a context, 18 months into Labour’s time in office, where it’s become evident that the public need to contribute more, to sustain public services and fix the country.

The ‘black hole’ rhetoric may at first glance seem consistent with the household budget analogy. And from a partisan Labour viewpoint it is doubtless pleasing, casting the Tories as the true party of Micawber. But as a ‘country over party’ justification for greater tax contributions it is problematic. It implies that the electorate are being asked to pay for the Treasury’s profligacy.

Labour may have expected that this profligacy could be pinned on the previous Tory administration. But the public – who really do put country before party – simply observe money being hoovered into the abyss, and dig their heels in.

For years it has been said that the UK is trying to run ‘Swedish public services on US tax rates’. For years it has been acknowledged that, for social democracy to function, this equation needs to be rebalanced. And for years, social democrats have looked at this problem with trepidation, usually choosing to duck it. Most recognise the political risks attached, thanks to their parties’ reputations for economic mismanagement. All they can do, they feel, is project frugality to the markets and hope for growth.

The result for the country, ironically, is very similar to the Micawber mode of running a household: enjoy the fruits of a world-class NHS, but put off the attendant tax increases for another day. Indeed, as the academic Jo Mitchell points out, the ‘black hole’ in fact describes a simple shortfall between the government’s income and its outgoings. If it had been explained in this way, then perhaps voters would have been less hostile to the tax increases the country needs.

I believe that there are ways around this in the future: by separating Micawber’s Law from the idea the left doesn’t ‘get’ aspiration; by blending fiscal conservatism and economic radicalism. The need for progressive taxes can be met – if the psychology of Micawber’s Law is properly understood.

There are four steps here, I believe. The first is to link the revenue raised by taxes to an immediate and popular outcome, so the public are clearly getting something in return – i.e. a universal service we all need and use, improvements in which are noticed. This must, as I have said, be separate from debt, black holes, arrears and the public accounts.

Secondly, the more that Treasury money can be ring-fenced, earmarked and hypothecated towards specific policies and causes, the better. A tax rise can only override Micawber’s Law if money moves directly from one place to another, demonstrating an ability to prioritise and a transparency about where taxes are going.

Thirdly, there needs to be a clear sense that revenue is being well-spent. Public sector reform should not be seen as something right-wing or even ‘centrist’, if it’s simply about making public money go further.

And fourthly, growth should be stripped from the language and the assumptions on offer, and treated as a welcome bonus if it happens. The promise of growth can in fact make a government appear like Micawber, hopeful that a dramatic uptick in GDP will ‘turn up’, and ready to price this uptick into your calculations before it’s happened.

An extremely good example of these steps being taken was Gordon Brown’s 2002 increase in National Insurance. This was badged as going directly towards the NHS, and was broadly accepted as a result by the public – especially as waiting lists did in fact fall. It was an alternative to borrowing (remaining consistent with Brown’s Golden Rules). It was accompanied by New Labour’s NHS reforms, creating a clear imperative that the money was spent well. And it did not rely on a dubious promise of growth (although growth did in fact happen, partly thanks to a healthier population).

A more recent case study is the removal of tax exemptions for private schools by Keir Starmer – proceeds of which were earmarked for state education. Right-wing attempts to portray this as an attack on aspiration did not stand up because it was obvious that need was greater elsewhere.

Both examples borrow a little of the zero-sum logic of the household budget. In each case, policy-makers transparently move cash from one column to another, without dipping into the red. Hard-earned taxes aren’t absorbed into the Treasury vortex or spent paying off someone else’s debts. ‘Fiscal conservatism and economic radicalism’ align.

Micawber’s Law ultimately guides the tempo and pattern of UK politics. In a focus group I once did, a voter put this as follows: ‘The Tories usually win. But after a while you need Labour to go and chuck some money at things. Then you bring the Tories back to sort out the mess.’ As an epigram for the historic cycle of British politics this is hard to beat.

There were two things which particularly struck me about the comment – and the round of nods and murmurs of agreement which greeted it from the other focus group participants.

The first is that Labour’s alleged overspending is often priced in. The party’s largess is deemed necessary for short stints, when Conservative penny-pinching has become too much to bear. But afterwards people usually go back to the Tories – who, for all their faults, they trust to apply restraint. Prolonged periods of Tory drought, after which Labour is briefly permitted to turn on the taps.

In this light, Labour’s continued focus on fiscal rectitude after coming into office in July 2024 has potentially thrown voters. They want Labour to show it is not the reckless party of Micawber before it gets in. But they nevertheless assume there is more money to be found within the government coffers, once a party with more generous instincts is ensconced.

This is not to say the answer in 2024 should have been to throw caution to the wind or rip up the fiscal rules. But the extent to which Rachel Reeves meant what she said – and the extent to which this has limited the scope for the ‘change’ promised – goes someway to explaining the brevity of the Labour honeymoon.

The second aspect of the above quote which struck me was its reliance on a two-party system. Labour and the Conservatives are often viewed by swing voters as two weathermen, one overly wasteful, the one overly frugal. Labour exists – very unsatisfactorily from the perspective of its own supporters – to sporadically compensate for the necessary meanness of the Tories.

In a context where the latter have sunk without trace (albeit with recent signs of life), there is a serious question about what the new dynamic looks like. Assuming the Conservatives do properly return, it’s unclear whether this will be as the flag-bearers of fiscal responsibility or as something completely different. In the meantime, Labour holds the crown of prudence, but seems to take little pleasure in wearing it. Voters on Labour’s left may once have supported the party, knowing that its focus on budgetary discipline – whilst never going to set their own pulses racing – was necessary to win. Now, they wonder what it’s all for.

Both of these points mean we are at a critical moment for the household budget analogy and Micawber’s Law. Starmer and Reeves have an opportunity to shed, once and for all, their party’s unhelpful reputation for profligacy. But there are serious questions about whether Labour can retain its progressive and traditional bases at the same time, in a context where there is not a harsher and more austere alternative waiting in the wings, in the form of the Tories. Can Labour be the primary champion of fiscal rectitude, whilst mobilising the emergent left bloc in British politics?

To conclude, it is worth thinking of the 1945-50 Labour government. This is a better case study than either of the more recent examples mentioned above, when it comes to the elusive combination of ‘fiscal conservatism and economic radicalism’. The NHS was founded, the welfare state was created, and the first generation of social housing was rolled out. Yet this happened against a backdrop of rationing and Crippsian austerity. Nye Bevan, the most prominent left-winger in the cabinet, heralded the ‘language of priorities’ as his guiding light.

This building of a New Jerusalem was of course helped by the fact that tax rises had been introduced before the Labour government was voted in, during the war years. It was also helped by a pre-globalisation context, where the economy was perhaps a little more like a discrete ‘household’ than it is today.

Yet the achievements of 1945-50 do, I think, hold lessons for modern leaders. They prove that the zero-sum politics of scarcity and sacrifice can co-exist with the sense of an active and progressive government, making positive choices on behalf of the public.

As the current government enters a make-or-break year, it needs to consider carefully the lessons this holds in the modern context. Through a detailed and forensic understanding of the household budget analogy, there are ways to overcome Micawber’s Law once and for all.